A lot of people buy their guns based on what is popular at the time, what appears on gun magazine covers, or what a trusted source recommends. They don’t care about technical details. They just want to know if it’s going to be reliable and accurate.

Technically minded customers, however, will ask questions, and it is highly likely that they already know the answers before they ask. That means that you, as the local gun seller, also need to know. One topic that may come up is the difference between conventional rifling versus polygonal rifling — especially if you’re selling some of the popular brands that list polygonal rifling as one of their selling points. These include guns made by Glock, H&K, Walther, Kahr Arms and others.

To explain the differences between polygonal and conventional rifling, we need to look back into history for a lesson. When firearms first became popular, they used smoothbores with no rifling. These worked well but were notorious for their lack of accuracy. In the mid 19th century, gunmakers began experimenting with cutting spiral grooves inside the barrels to make bullets spin in flight. The result was a more stable and accurate projectile. The process involved using a special scraper to make the twisting cuts around the inside of the bore. The cut portions are referred to as grooves, and the remaining uncut portions are known as lands. This method is referred to as conventional or standard rifling and remains the primary type of rifling seen in most firearms.

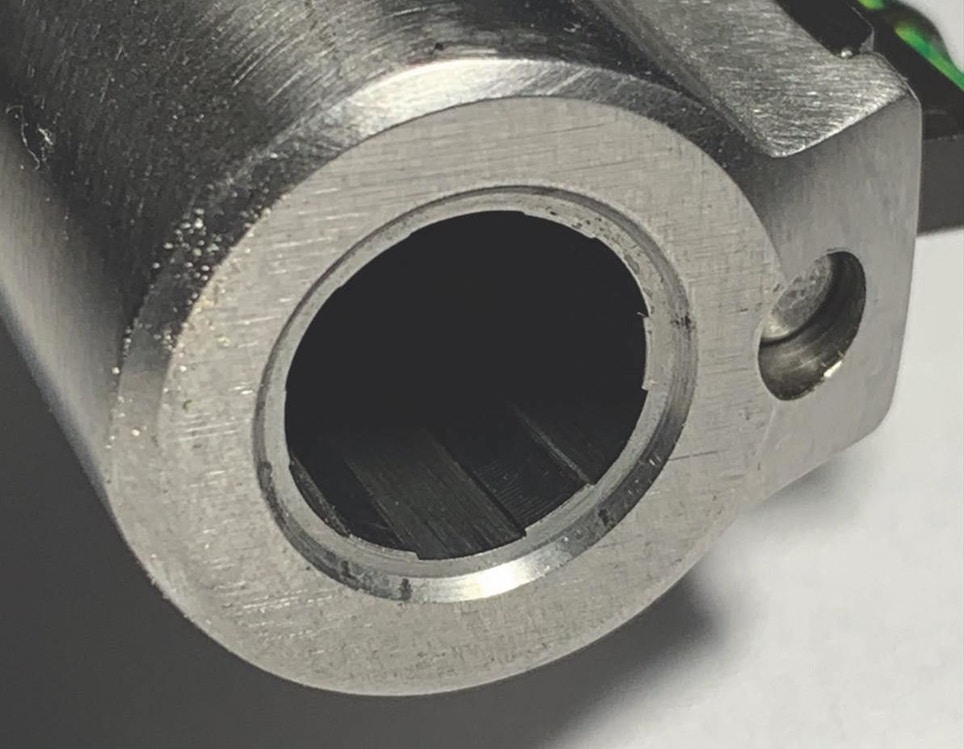

While this was going on, Joseph Whitworth was commissioned by the British government to improve the inaccurate and inconsistently produced Enfield rifle that was then in service. Whitworth was a mechanical engineer famed for producing precision tools. Since his specialty was making precision equipment to machine surfaces perfectly flat, he decided to create a barrel using multiple flat surfaces rather than simply cutting grooves into a round barrel’s bore. He had previously designed a cannon utilizing that technique, so he adapted it to his rifle design, thus inventing polygonal rifling. When looking at the muzzle of one of his barrels, it looked like a hexagonal or octagonal bore.

Making his rifle accurate wasn’t as simple as just producing great barrels. He also had to redesign the traditional bullets that were in use. Knowing his love for precision equipment, it shouldn’t be surprising that he machined his bullets in the same pattern as his barrels. No longer were soft lead bullets needed to allow the traditional rifling to deform them to match the barrel’s rifling. His bullets were machined to make a very tight fit, but his work still wasn’t complete.

The next stage was to experiment with different spiral rates to find one with enough twists to stabilize the bullet and prevent tumbling (he ended up with a 1:20 twist). Then, like modern precision shooters, he had to carefully test for the correct bullet weight and powder charge to make the entire system work together. The end result produced incredible and consistent accuracy. His design was so successful that he won the contract to build Whitworth rifles for the British government.

On a side note, there is a fascinating account of Queen Victoria pulling the trigger on one of Whitworth’s rifles at the inaugural meeting of the National Rifle Association of the U.K. on July 2, 1860. The rifle had been placed on a stand and aimed at a target 400 yards away. This first shot landed 1.25 inches from the target’s center. In modern terminology, this is 1/3 MOA. Today, 1 MOA is considered accurate. The rifle’s success didn’t go unnoticed, and some of them were purchased by the Confederates during the U.S. Civil War. They quickly earned a reputation with Confederate sharpshooters as superior to the Union Army’s Sharps rifle.

In World War II, the German army needed a way to produce high volumes of barrels for their MG42 machine gun, which was notorious for wearing out barrels due to its high rate of fire. German engineers created a process before the war called cold-hammer forging, where the barrels were hammered into shape around a precisely formed and polished polygonal mandrel. The German army adopted this new process and polygonal rifling, allowing them to produce barrels much faster and at much less cost than the Allies. Once again, Whitworth’s design met a critical need.

Modern Polygonal Barrels

In 1981, Gaston Glock invented a polymer-frame pistol for the Austrian army known as the Glock 17. It was light, held more 9mm rounds than any of its competitors, and its reliable and straightforward design made it an instant hit. Glock pistols seemed to take the world by storm in the late 1980s. Law enforcement and military contracts fueled the public demand, and the Glock 17 became one of, if not the most, popular pistols in the world. Polygonal rifling suddenly became a hot topic because it was a top selling point as well as a top criticism of Glock pistols. The questions still echo at the gun counter today as customers ask, “What is the advantage over conventional rifling?” and “Why does Glock recommend against using lead bullets?”

Here are the basics.

Polygonal rifling has some theoretical advantages over conventional rifling:

· It does not deform the bullet or cut into it the way traditional rifling does

· It offers a better bullet-to-barrel seal resulting in more consistent sealing of the gasses as the bullet travels down the barrel.

· It provides less friction and thus higher potential velocities.

· It is easier to clean than conventional rifling.

· The barrels last longer.

The major disadvantage (to some) is that cast lead bullets are not recommended with polygonal barrels. For those who like to shoot a lot, lead bullets have always been the go-to training ammunition because they are cheaper than jacketed bullets. Reloaders commonly use lead bullets for practice ammunition for the same reason. Using jacketed bullets raises the cost of shooting significantly.

The problem with using lead bullets with polygonal rifling is that there is a shearing effect when a soft, lead bullet travels through the bore. This can cause a buildup of lead in the barrel, leading to higher pressures and potentially catastrophic failures. Glock and H&K have found this during their testing, and many Glock owners who didn’t follow the guidelines against lead bullets have experienced catastrophic failures. The bottom line is to follow the recommendations when it comes to ammunition.

Lasting influence

Whitworth’s Rifles revolutionized precision shooting when introduced in 1859 and remained the standard for over a decade — essentially until breach-loaded weapons replaced them. They were used as sniper rifles by the military and as competition guns by civilians. This was possible as a result of using polygonal barrels and bullets designed by Joseph Whitworth.

This short history lesson answers the question of accuracy. For those needing a more modern answer, refer them to H&K precision rifles and even to LaRue Tactical’s decision to adopt polygonal barrels in their highly regarded AR-15 rifles.

From a practical standpoint, there is little accuracy difference between modern, conventional and polygonal rifling. In most instances, modern rifles tend to be more accurate than their owners are capable of shooting. So, explain the difference to your customer and be confident that no matter which rifling pattern they end up with, it will be accurate and reliable.

One final note: Make sure to invite them to bring in their targets and show them off. They’ll undoubtedly be looking for upgrades, so they might as well buy them from you.